Imagine standing 8,000 metres above the sea floor at Mount Everest, and you find a marine fossil. You should not be surprised because fossils of marine animals have been documented near the summit of Mount Everest, findings that continue to draw scientific and public interest. Climbers and geologists have reported remains of trilobites, crinoids and brachiopods embedded high in the Himalayas. These fossils are not recent intrusions. They are part of sedimentary rock formed millions of years before the mountain existed. Their presence reflects deep geological change linked to plate tectonics and the long closure of an ancient ocean. Evidence gathered over decades connects these marine deposits to the former Tethys Ocean, which once separated the Indian landmass from Asia. The rocks now exposed at extreme altitude were once laid down beneath seawater, later lifted as continents converged.

Fossil seashells on Everest confirm the Himalayas were once under the sea

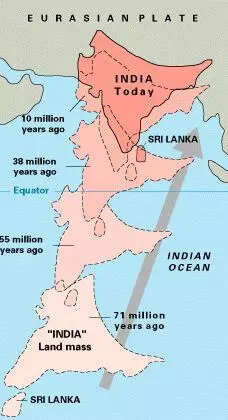

According to The Geology Society, Everest’s summit is formed on the floor of the Tethys Ocean. Around 225 million years ago, the Indian plate sat far south of Asia, separated by this broad ocean basin. Sediments accumulated along its margins. Shells and skeletal fragments settled into layers that slowly hardened into rock.These layers remained in place as tectonic forces reshaped the region. The fossils seen today are ordinary marine organisms from that distant period. Their height above sea level is what seems unusual.

Indian plate drift reshaped the region (Image Source – The Geology Society)

Indian plate drift reshaped the region

When the supercontinent Pangaea began to fragment about 200 million years ago, the Indian plate started moving north. By 80 million years ago it was thousands of kilometres south of Asia but advancing steadily. The oceanic crust of the Tethys was pushed beneath the Eurasian margin in a subduction zone, similar in setting to the Andes today.Not all material disappeared underground. Thick marine sediments were scraped off and pressed against the Eurasian edge. Over time these accumulated sediments became part of the rising mountain belt.

Himalayas continue to uplift 1 cm every year

Between 50 and 40 million years ago, the Indian and Eurasian continental plates collided. Neither plate could sink easily because both were buoyant continental crust. Instead, the crust crumpled, thickened and lifted. The collision marked the start of Himalayan uplift.The Himalayas stretch roughly 2,900 kilometres east to west. Mount Everest reaches 8,848 metres, the highest point on Earth. Geological measurements indicate the range is still rising by more than one centimetre per year as India continues to press northward. At the same time, erosion works in the opposite direction. Rock is worn down by ice, wind and water. The balance shifts slowly. Fossils remain in place, quiet traces of a sea that once covered what is now the roof of the world.